THE JOINTER

This article is from Issue 47 of Woodcraft Magazine.

Working on the straight and true.

The jointer belongs to the trinity of stock-dressing machines that also includes the table saw and thicknesser. Of those, it’s probably the most misunderstood. Although its job is simple–straightening and flattening stock–the tool frustrates many woodworkers because jointing requires a certain finesse. However, when set up and used properly, a jointer will do its job precisely and efficiently in a way that no other machine can.

I’ll show you how to put this remarkable machine to work in a way that speeds up your woodworking while ensuring accuracy and quality of cut.

Before we get started, it’s important to note that a jointer–more so than most other machines–must be precisely tuned to work properly.

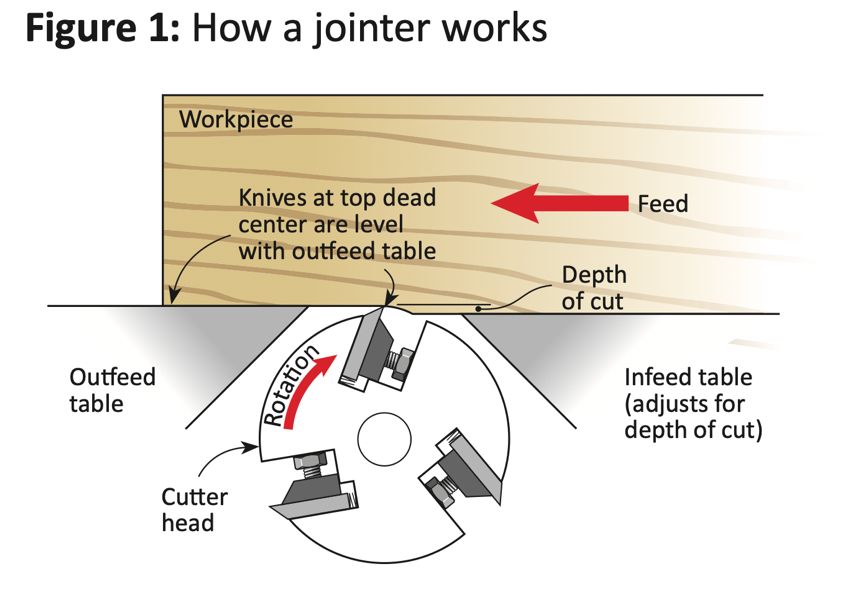

With a jointer, a workpiece fed across the infeed table is cut by knives that are set at top dead centre to the height of the outfeed table, as shown in Figure 1. The outfeed table supports the cut surface as the remainder of the board is jointed. This is why it’s so important that the tables are parallel to each other. If they’re not, or if the knives are set too high or low, a straight cut won’t result. To eliminate or minimize tear-out, orient the workpiece so the knives rotate in the same direction as the slope of the grain, as shown.

What It Will & Won’t Do

The bulk of a jointer’s chores involves edge-jointing and face-jointing, which I’ll address in this article. It can also cut chamfers, rabbets, bevels, and tapers, but those are tricks for another time. It’s important to note that a jointer cannot be expected to mill a board to consistent thickness. That’s a job for the thicknesser. Although the jointer can remove wood from both faces in turn, the result is almost certain to be a tapered board.

Working on the straight and true.

The jointer belongs to the trinity of stock-dressing machines that also includes the table saw and thicknesser. Of those, it’s probably the most misunderstood. Although its job is simple–straightening and flattening stock–the tool frustrates many woodworkers because jointing requires a certain finesse. However, when set up and used properly, a jointer will do its job precisely and efficiently in a way that no other machine can.

I’ll show you how to put this remarkable machine to work in a way that speeds up your woodworking while ensuring accuracy and quality of cut.

Before we get started, it’s important to note that a jointer–more so than most other machines–must be precisely tuned to work properly.

With a jointer, a workpiece fed across the infeed table is cut by knives that are set at top dead centre to the height of the outfeed table, as shown in Figure 1. The outfeed table supports the cut surface as the remainder of the board is jointed. This is why it’s so important that the tables are parallel to each other. If they’re not, or if the knives are set too high or low, a straight cut won’t result. To eliminate or minimize tear-out, orient the workpiece so the knives rotate in the same direction as the slope of the grain, as shown.

What It Will & Won’t Do

The bulk of a jointer’s chores involves edge-jointing and face-jointing, which I’ll address in this article. It can also cut chamfers, rabbets, bevels, and tapers, but those are tricks for another time. It’s important to note that a jointer cannot be expected to mill a board to consistent thickness. That’s a job for the thicknesser. Although the jointer can remove wood from both faces in turn, the result is almost certain to be a tapered board.

Planning the cut

Before making a cut, you’ll need to decide how to best orient the piece for feeding and how deep a cut to make. How you orient a board depends on its warp (Figure 2) and the slope of its grain. For stability when feeding, place the concave face or edge against the jointer tables. When face-jointing, this means you should orient the cup or bow downward. When edge-jointing, the crook should be at the bottom. That way, the board will ride on its high spots, providing better footing. Conversely, if you try to feed with the convex side downward, the board will rock, making control difficult.

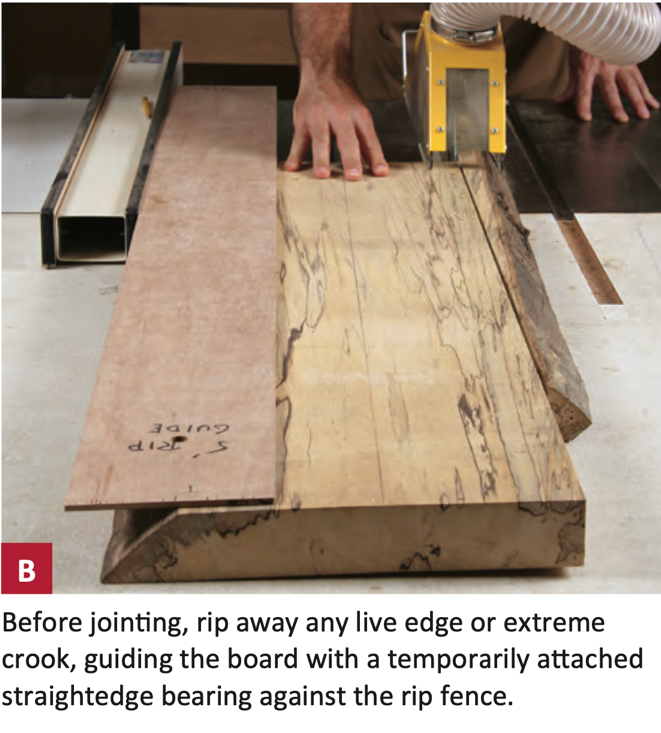

Begin by sighting down the edge of a board (Photo A). This will clearly reveal any bow or crook at the same time. (If a board has an extreme crook, saw it away first, in the same way you would rip away a live edge, as shown in Photo B.) Cup is generally evident at a glance, but you can sight across the end of the board to be sure.

After determining which edge or face gets fed downward, orient the board so the knives will rotate with the direction of the grain slope (Figure 1) instead of against it, which can cause tear-out. Of course, grain often doesn’t run neatly in one direction only. If it reverses, just favour the direction that cuts mostly with the slope.

Before making a cut, you’ll need to decide how to best orient the piece for feeding and how deep a cut to make. How you orient a board depends on its warp (Figure 2) and the slope of its grain. For stability when feeding, place the concave face or edge against the jointer tables. When face-jointing, this means you should orient the cup or bow downward. When edge-jointing, the crook should be at the bottom. That way, the board will ride on its high spots, providing better footing. Conversely, if you try to feed with the convex side downward, the board will rock, making control difficult.

Begin by sighting down the edge of a board (Photo A). This will clearly reveal any bow or crook at the same time. (If a board has an extreme crook, saw it away first, in the same way you would rip away a live edge, as shown in Photo B.) Cup is generally evident at a glance, but you can sight across the end of the board to be sure.

After determining which edge or face gets fed downward, orient the board so the knives will rotate with the direction of the grain slope (Figure 1) instead of against it, which can cause tear-out. Of course, grain often doesn’t run neatly in one direction only. If it reverses, just favour the direction that cuts mostly with the slope.

Finally, set the jointer for an appropriate depth of cut. If you don’t have to remove a lot of material, take lighter cuts to avoid wasting stock or overcutting the piece. However, if you’re jointing rough-sawn and/or badly warped boards, you’ll work faster with a deeper cut. For general use, I leave my machine set for a 1⁄32"-deep cut, which is just about right for removing saw marks on a ripped edge. For the heaviest milling, I cut about 1⁄8" deep per pass.

General feeding principles

Successful jointing depends on the proper body stance, feed pressure, and feed speed. There’s a certain amount of nuance involved, but you should be able to nail it with a bit of practice.

When feeding, begin by standing with your feet splayed for good footing. Lay the board fully on the infeed table just in front of the cutterhead guard, pressing the leading end down firmly. Push the board forward while maintaining downward pressure at the leading end and forward pressure at the trailing end. As you move along with the board, waltz sideways by bringing your right foot against the left; then step widely sideways again. When your belt buckle is about 10" rearward of the cutterhead, plant yourself there and complete the cut by moving the board forward with your hands, maintaining downward pressure over both the infeed and outfeed tables without overreaching.

Avoid applying excessive downward pressure when face-jointing thin stock or edge-jointing narrow pieces that flex. The idea of jointing is to gradually remove the high spots in order to bring the surface into a flat plane. Therefore, you don’t want to press a flexible piece into full contact with the tables during feeding. Instead, press down just enough to keep the knives from slapping the piece upward.

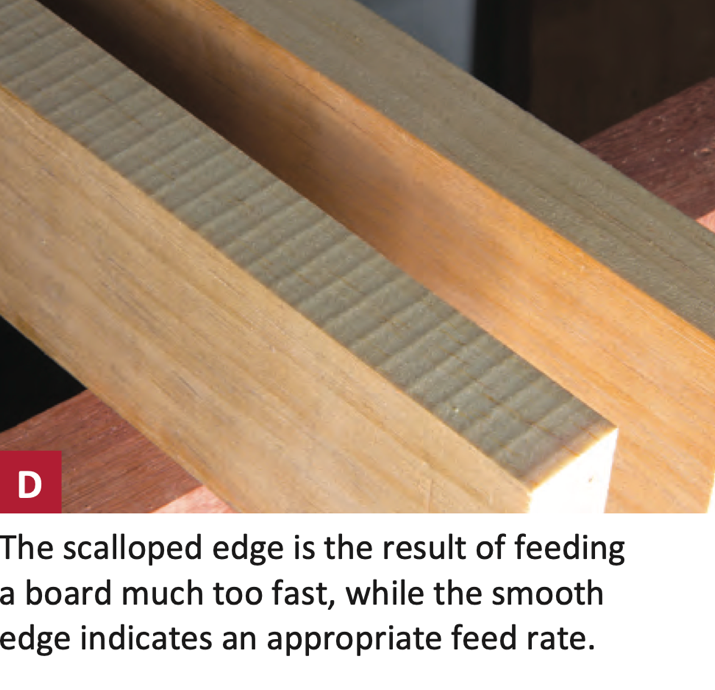

Proper feed speed depends on the density of the wood, the width of the piece, and the depth of cut. Your best gauge of the proper feed rate is the cut itself (Photo D). Moving too quickly creates a scalloped surface. On the other hand, moving too slowly won’t normally hurt the surface, but it wastes time. Taking a couple practice passes and then inspecting the resulting surface should tell you what you need to know.

Successful jointing depends on the proper body stance, feed pressure, and feed speed. There’s a certain amount of nuance involved, but you should be able to nail it with a bit of practice.

When feeding, begin by standing with your feet splayed for good footing. Lay the board fully on the infeed table just in front of the cutterhead guard, pressing the leading end down firmly. Push the board forward while maintaining downward pressure at the leading end and forward pressure at the trailing end. As you move along with the board, waltz sideways by bringing your right foot against the left; then step widely sideways again. When your belt buckle is about 10" rearward of the cutterhead, plant yourself there and complete the cut by moving the board forward with your hands, maintaining downward pressure over both the infeed and outfeed tables without overreaching.

Avoid applying excessive downward pressure when face-jointing thin stock or edge-jointing narrow pieces that flex. The idea of jointing is to gradually remove the high spots in order to bring the surface into a flat plane. Therefore, you don’t want to press a flexible piece into full contact with the tables during feeding. Instead, press down just enough to keep the knives from slapping the piece upward.

Proper feed speed depends on the density of the wood, the width of the piece, and the depth of cut. Your best gauge of the proper feed rate is the cut itself (Photo D). Moving too quickly creates a scalloped surface. On the other hand, moving too slowly won’t normally hurt the surface, but it wastes time. Taking a couple practice passes and then inspecting the resulting surface should tell you what you need to know.

Always us push sticks a shoe shaped one for edges and flat one with a heal for boards.

Next, orient each piece as discussed earlier–with the concave face down and the grain sloping in the direction of the cut. (If necessary to read the edge grain, take a quick pass or two off the edge.) If cup and bow are on opposite faces, lay each face of the piece on the table in turn, rock it to see which orientation is more stable, and go with that orientation.

When setting your depth of cut, err on the shallow side for starters. Then take a test cut. If desirable, increase the depth of cut for efficiency. Again, the maximum cut will depend on the width and density of the workpiece, but I generally don’t remove more than about 1⁄8" at a time.

For pieces that aren’t much longer than your infeed table, hook your heeled push block onto the trailing end of the board. Hold down the leading end of the board with your left hand (or use a non-heeled push block for stock thinner than about 3⁄4"); then feed the board across the cutterhead. Repeat as necessary until the face is flat.

Beginning the cut, make sure your heeled push block is within reach. (I set mine on the jointer behind the fence.) Lay the board’s leading end fully on the infeed table, supporting the trailing end with your right hand. With your left hand, reach as far forward as you comfortably can to press the leading end of the board against the table. Feed the board forward while providing enough upward support at the trailing end to maintain contact with the table. When the board is fully at rest on the tables, grab your push block and complete the cut.

Face-jointing long boardsSupport the cantilevered trailing end of a long board at its rear edge halfway down the length of the board.

Basic edge-jointingThe purpose of jointing an edge is not only to straighten it, but usually to square it up to a board’s face(s) as well, so make sure your jointer fence is accurately set to 90°. Orient your workpieces ahead of time with any crook downward and with the grain slope favouring the cut, as discussed earlier.

The trick to getting a square edge is to keep the previously jointed face of the board in intimate contact with the fence throughout the cut. At the same time, you need to protect your hands from that potentially vicious cutterhead. Try this approach, which ensures stable feeding even on a small jointer with a low fence.

Begin with the board’s leading end a few inches from the cutterhead, and press the board against the fence. The key here is to splay the fingers of your left hand so that they apply pressure at both the top and bottom edges of the fence, while pressing downward with your thumb at the same time. As you approach the guard, raise your lower fingers safely above it while maintaining pressure against the fence. Once past the guard, drop your lower fingers again.

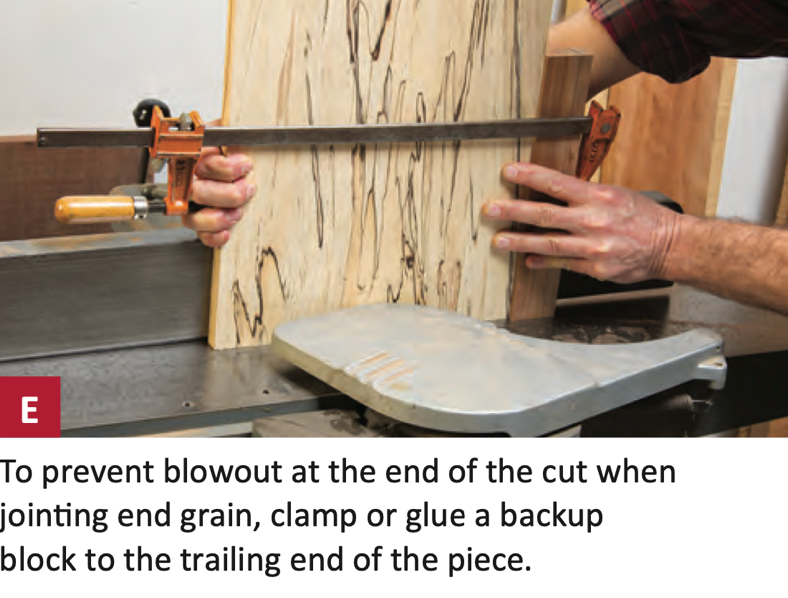

Yes, it’s possible to joint end grain. The only issue is that the unsupported fibres at the trailing end of the cut tend to break away. To prevent that, just back up the workpiece. One approach for shorter pieces is to clamp on a support block, as shown in Photo E. For larger pieces, where a clamp would be unwieldy, you can temporarily glue the block in place. When jointing end grain, it’s best to take a light cut–no more than about 1⁄32"

When setting your depth of cut, err on the shallow side for starters. Then take a test cut. If desirable, increase the depth of cut for efficiency. Again, the maximum cut will depend on the width and density of the workpiece, but I generally don’t remove more than about 1⁄8" at a time.

For pieces that aren’t much longer than your infeed table, hook your heeled push block onto the trailing end of the board. Hold down the leading end of the board with your left hand (or use a non-heeled push block for stock thinner than about 3⁄4"); then feed the board across the cutterhead. Repeat as necessary until the face is flat.

Beginning the cut, make sure your heeled push block is within reach. (I set mine on the jointer behind the fence.) Lay the board’s leading end fully on the infeed table, supporting the trailing end with your right hand. With your left hand, reach as far forward as you comfortably can to press the leading end of the board against the table. Feed the board forward while providing enough upward support at the trailing end to maintain contact with the table. When the board is fully at rest on the tables, grab your push block and complete the cut.

Face-jointing long boardsSupport the cantilevered trailing end of a long board at its rear edge halfway down the length of the board.

Basic edge-jointingThe purpose of jointing an edge is not only to straighten it, but usually to square it up to a board’s face(s) as well, so make sure your jointer fence is accurately set to 90°. Orient your workpieces ahead of time with any crook downward and with the grain slope favouring the cut, as discussed earlier.

The trick to getting a square edge is to keep the previously jointed face of the board in intimate contact with the fence throughout the cut. At the same time, you need to protect your hands from that potentially vicious cutterhead. Try this approach, which ensures stable feeding even on a small jointer with a low fence.

Begin with the board’s leading end a few inches from the cutterhead, and press the board against the fence. The key here is to splay the fingers of your left hand so that they apply pressure at both the top and bottom edges of the fence, while pressing downward with your thumb at the same time. As you approach the guard, raise your lower fingers safely above it while maintaining pressure against the fence. Once past the guard, drop your lower fingers again.

Yes, it’s possible to joint end grain. The only issue is that the unsupported fibres at the trailing end of the cut tend to break away. To prevent that, just back up the workpiece. One approach for shorter pieces is to clamp on a support block, as shown in Photo E. For larger pieces, where a clamp would be unwieldy, you can temporarily glue the block in place. When jointing end grain, it’s best to take a light cut–no more than about 1⁄32"

Edge-jointing long boardsLong boards–particularly if they’re wide and heavy–can be frustrating to edge joint. Part of the problem is that a long board tends to arc over the tables. Invert the picture, and it’s akin to the way that a short hand plane dips into the hollow of a crooked edge. Just as a longer hand plane shoots an edge better, a longer jointer is better suited to handling long boards.

The other problem is handling a long board–particularly if it’s also wide and heavy. Unfortunately, using auxiliary feed supports is of little help because it’s virtually impossible to adjust them precisely level with the jointer tables. That’s okay. With a bit of practice, you can learn to successfully manoeuvre a long board on the jointer.

Try this approach, as shown in the photos above. Turn the machine on. Then, supporting the board on edge at its centre, lay its leading end fully onto the infeed table. Rock it up and down a bit, observing and feeling when it contacts the front and rear end of the infeed table. Level it out as best you can and hold it at that level as you manoeuvre it sideways against the fence. Peer over the back of the board to monitor the contact against the fence.

Now begin feeding forward while continuing to monitor the contact between the board and the fence. When the full weight of the board is on the tables, move closer to the centre of the jointer for better control. As you approach the end of the cut, increase your pressure on the trailing end of the board to prevent the leading end from dropping. If you’re careful throughout this procedure, your stability will increase with every pass as the cut conforms to the intersection between the tables and fence.

This article is reprinted from Issue 47 of Woodcraft Magazine.

The other problem is handling a long board–particularly if it’s also wide and heavy. Unfortunately, using auxiliary feed supports is of little help because it’s virtually impossible to adjust them precisely level with the jointer tables. That’s okay. With a bit of practice, you can learn to successfully manoeuvre a long board on the jointer.

Try this approach, as shown in the photos above. Turn the machine on. Then, supporting the board on edge at its centre, lay its leading end fully onto the infeed table. Rock it up and down a bit, observing and feeling when it contacts the front and rear end of the infeed table. Level it out as best you can and hold it at that level as you manoeuvre it sideways against the fence. Peer over the back of the board to monitor the contact against the fence.

Now begin feeding forward while continuing to monitor the contact between the board and the fence. When the full weight of the board is on the tables, move closer to the centre of the jointer for better control. As you approach the end of the cut, increase your pressure on the trailing end of the board to prevent the leading end from dropping. If you’re careful throughout this procedure, your stability will increase with every pass as the cut conforms to the intersection between the tables and fence.

This article is reprinted from Issue 47 of Woodcraft Magazine.